On Brexit: Dining with a European ally & reviewing Scottish & Polish links

With the prorogation of Parliament underway, and the October Brexit deadline looming, the merest thought of Boris Johnson is enough to give me indigestion.

So in the spirit of cooperation and solidarity, I’m dining with a European ally, the chairperson of the Scottish Polish Cultural Association in Edinburgh, Izabella Brodzinska.

In the hope of taking our minds off the state of politics, and the jiggery-pokery going on at Westminster, we plan to comfort eat our way through a menu of Polskie fare on offer at Percy’s restaurant on Edinburgh’s Easter Road.

Our countries have a rich entwined history; Bonnie Prince Charlie aka Charles Edward Stuart was half Polish, his mother Maria Klementyna Sobieska, was the granddaughter of the king.

I was surprised to find out that Scottish migration started back in the 14th/15th centuries when merchants were welcomed to the Baltic with trade agreements between Aberdeen and Danzig, now Gdansk.

Around 30,000 Scots relocated to take advantage of these new business opportunities.

Today there are still Scottish place names like Nowa Szkocja (New Scotland) and Izabella tells me that a quick glance in the phone directory will show you Polonised Scottish surnames — for example, Czamer (Chalmers), Dziaksen (Jackson), Machlejd (MacLeod), Szynkler (Sinclair).

Today there are still Scottish place names like Nowa Szkocja (New Scotland) and Izabella tells me that a quick glance in the phone directory will show you Polonised Scottish surnames — for example, Czamer (Chalmers), Dziaksen (Jackson), Machlejd (MacLeod), Szynkler (Sinclair).

Over the centuries our merchants prospered. Alexander Chalmers, from Dyce, became a judge and four times mayor of Warsaw, while Robert Gordon (of university fame) earned his fortune abroad before becoming an educational benefactor.

The German invasion of Poland in 1939 marked the beginning of World War Two.

Polskie soldiers were forced to regroup in exile, and many were based here and played a huge part in the war effort, fighting alongside us.

Polskie soldiers were forced to regroup in exile, and many were based here and played a huge part in the war effort, fighting alongside us.

After the war, the troop divisions were disbanded but many former servicemen were forced to remain in exile.

These included Izabella’s father; she only travelled to Scotland to meet him in person in 1957 aged 17.

These included Izabella’s father; she only travelled to Scotland to meet him in person in 1957 aged 17.

Today Scotland attracts a new wave of young Poles; there are 87,000 Polish folk living here, which makes up a quarter of the non-British population, according to the 2018 population report from the National Records of Scotland.

They are attracted in part by our shared history, the quality of life here, work opportunities and freedom of movement.

Percy’s interior is classic with red roses in glass bottles and the menu is packed with traditional delicacies such as Smalec, a salty spread of rendered pork fat served with soured gherkins and bread, plus pan-fried herring presented with a frozen shot of Wyborowa vodka to put fire in your belly.

Both Scotch whisky and Polish vodka are on offer here, along with Tymbark soft fruit juices, a “taste of childhood for every Polak”, so I’m guessing our equivalent of Irn Bru.

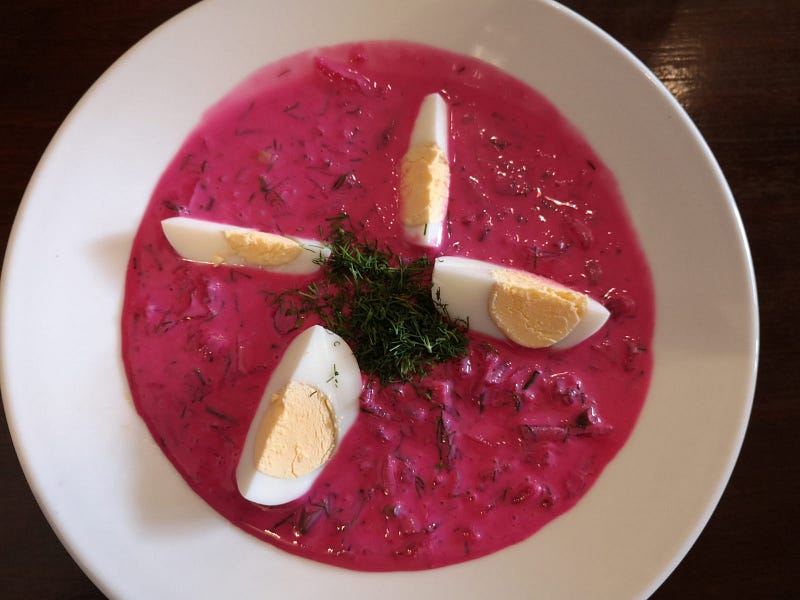

I heed the advice of my dining companion and sample a delicious Chlodnik.

A bright pink creamy soup made from beetroot, radish and yoghurt and decorated with a quartered boiled egg which is served cold, this is a robust plateful and I wasn’t sure whether to use my spoon or a knife and fork.

A bright pink creamy soup made from beetroot, radish and yoghurt and decorated with a quartered boiled egg which is served cold, this is a robust plateful and I wasn’t sure whether to use my spoon or a knife and fork.

Izabella opts for the impressive Zurek Bread bowl, a wholesome rye broth with chunks of Polish white sausage and egg.

The soup is served hidden inside the hollowed-out rye bread loaf, which magically keeps its liquid innards from spilling out, strangely reminding me of the state of the European Union.

The soup is served hidden inside the hollowed-out rye bread loaf, which magically keeps its liquid innards from spilling out, strangely reminding me of the state of the European Union.

Hit by Brexit blues again, I order a side of crunchy dill pickled cucumbers to accompany my main course of pan-fried Pierogi parcels.

A comforting helping of sour cabbage and mushroom dumplings, these half-moon packets have crimped edges and are topped with salty fried caramelised onions.

My new pal opts for a traditional steamed version of Pierogi, stuffed with cheese and potato topped with onions.

My new pal opts for a traditional steamed version of Pierogi, stuffed with cheese and potato topped with onions.

Looking around I spy a magnificent plateful heading to another table, a groaning mixed grill platter containing beef, pork, chicken, black pudding, white sausage with roast potato, tomatoes, pickles, salad, chips and garlic sauce.

A neighbouring diner scoffs an enormous breaded pork Schab or chop, which comes served with mashed tatties and fried sour cabbage.

The desserts are chalked up on a board and Izabella explains the different options.

I sample the traditional apple Szarlotka, a traditional warmed apple and cinnamon cake with icing sugar sprinkled liberally on top.

I sample the traditional apple Szarlotka, a traditional warmed apple and cinnamon cake with icing sugar sprinkled liberally on top.

This produces a warm glow of satisfaction, take note you will not be allowed to leave here hungry.

My first Polish food adventure has been a success, with my Brexit black mood lifting with kindness, commonality and friendship, and a timely reminder that we’re a’ Jock Tamson’s bairns.

Comments

Post a Comment